–

–

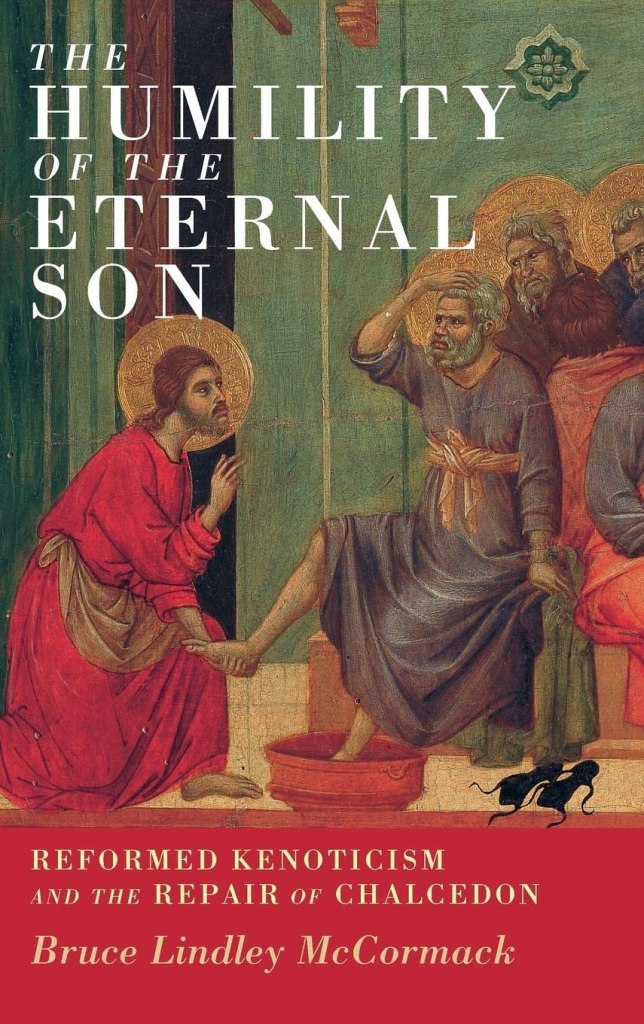

I am much too late to the game with Bruce McCormack’s study on Christology, The Humility of the Eternal Son. I am thankful to be done with it finally so that I can share a few quotes from the book and comment on the overall experience. The quotes I will be pulling from are from the very last chapter where he is summarizing his argument and responding to practical rebuttals to what he is proposing.

McCormack here, as hinted at in the subtitle, attempts a “repair” of the Chalcedonian Definition; as a faulty statement, he claims, about the full truth regarding Jesus Christ’s ontological makeup as both God and human, the Chalcedonian Definition has at its core a “logical aporia” (his term). By “logical aporia” he means a contradiction in the Definition which ultimately only pays lip service to the “side” of Jesus Christ that is fully human. McCormack explains this by writing that the Definition is funded by “Cyrilline” presuppositions concerning divine being. The fault in the Definition, grounded in these presuppositions, is that it claims the reality of Jesus is constituted by the Eternal Logos’s instrumentalization of human flesh. Although the orthodox theologians affirmed that – against Apollinaris – the Logos had taken on the entire reality that is human nature, in function they refused to concede that the Eternal Logos was affected by the union like the human nature was affected in being assumed by the Logos. The problem, ultimately, for McCormack, is how to situate the Christological subject. What constitutes, ontologically, the reality that is Jesus Christ? To McCormack, if the Logos is not affected by Jesus as Jesus is affected by the Logos, then the Definition’s claim that it safeguards the integrities of both natures is empty and groundless. This is so because “the attributes of both ‘natures’ must be ‘communicated’ to the Logos is he is to be the single Christological subject.”[1]

When I read the first chapter of this book, I felt both perplexed and excited. McCormack is telling his reader he aims to wade through the history of theological reflection, attempt a thorough investigation into a foundational doctrine of the Church, and then propose an essential reformulation of it. As someone interested in the history of theology, I was thrilled to slug through this book even though I had reservations about the prospects of its success. I get the sense that McCormack strays left of me, so to speak, in regards to his reverence for the Tradition. I will temper that claim, though, with an insightful remark of his:

“My point is this: we must be more ‘Chalcedonian’ than many of today’s defenders of Chalcedon are. We must not rest content with repeating words whose significance we have only dimly understood. We must do our Christology in the light of an appreciation for both the promise of Chalcedon and its limitations – and in that way, be truly ‘guided’ by it.”[2]

Amen and amen.

Perhaps the primary thought I came away with when reading this book – which is also how I have felt after putting down books by Torrance, Webster, et al. – is that this is an example of a theologian who has learned well from his master in the field, the inimitable Karl Barth. In McCormack’s (and Webster’s) case theirs wasn’t a direct, personal influence, but they nonetheless have been schooled in the fruitful halls of Barth’s post-metaphysical thought. Theological reflection, in the Barthian mode, is one I have always been convinced is creatively receptive. Theology is all the better for it.

What follows are a few quotes from his last chapter which do the work of appropriate theological speech:

“In the place of two discreet (substantially conceived) ‘natures’ subsisting in one and the same ‘person,’ I am going to posit the existence of a single composite hypostasis, constituted in time by means of what I will call the ‘ontological receptivity’ of the eternal Son to the ‘act of being’ proper to the human Jesus as human. ‘Ontological receptivity,’ it seems to me, is the most apt phrase for describing the precise nature of the relationship of the ‘Son’ to Jesus of Nazareth as witnessed to in the biblical texts we treated. I am going to argue further that it is the Son’s ‘ontological receptivity’ that makes an eternal act of ‘identification’ on the part of the Logos with the human Jesus to be constitutive of his identity as the second ‘person’ of the Trinity even before the actual uniting occurs. This is what I believe to have been missing in Jüngel and Jenson. The ‘Son’ has as ‘Son’ an eternal determination for incarnation and, therefore, for uniting through ‘receptivity.’ He is, in himself, ‘receptive.’”[3]

“Divine power, then, should never be understood in abstraction from what God actually does. It should be understood as the ability to accomplish all of that which God wills to do in the way God wills to do it – and nothing more. ‘Metaphysical compliments’ are excluded where the triune ‘being’ of God is understood to be constituted in purpose-driven trinitarian processions.”[4]

“The love that God is, is not love in general but a highly concrete and very specific kind of love. It is a self-giving, self-donating, self-emptying love. And it is the eschatological being of the Christian in Christ that they are called, even now, to imitate, to live from and towards, in their daily lives.”[5]

And finally:

“For what God is, God’s ‘essence’ is to be found in God’s livingness and nowhere else. Where God is concerned, we may not begin with the question of what God is or even with the question of who God is. We must begin with the question of the place of God’s livingness. Only there can we learn the answers to the questions of who and what God is.”[6]

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 52.

[2] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 29.

[3] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 252.

[4] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 267.

[5] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 276.

[6] Bruce McCormack, The Humility of the Eternal Son: Reformed Kenoticism and the Repair of Chalcedon (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 296.