–

Rudolf Bultmann is one of contemporary evangelicalism’s boogeymen. There are a number of theologians and biblical scholars who exist scribbled on the evangelical ret-con list, some more deserving of their placement on that list than others. As a dialectical theologian and higher critical New Testament scholar who wholeheartedly accepted the interpretive claims of German historico-critical scholarship in the twentieth century, Bultmann is on the more deserving side of that evangelical judgment. Christian theologians (lay or otherwise) are right to be careful when approaching his writings. The same can be said for theologians like Paul Tillich, who has a blog post or two dedicated to him here. Yet, reading Bultmann’s Jesus and the Word has turned out to be a more edifying endeavor halfway through the work than I thought would be the case when I decided to pick it up. To be sure, every other page or so features a scribbled note in the margin which expresses my constant inner cringing at the bleakness of Bultmann’s conception of my Lord; equally prevalent, though, are notes of mine which praise Bultmann’s obvious exegetical prowess and overall spiritual perception of the claims of Jesus.

I suppose it was inevitable that I would be reading Bultmann some day considering my reverence for Barth and Heidegger, two men who had profound influences on Bultmann as a theologian/scholar. One aspect of Bultmann’s Jesus and the Word which is at the heart of my own appreciation of Bultmann is his emphatic charge that existence and faith, according to Jesus, is not a neutral matter. Immediately, even from the beginning of the preface, Bultmann makes it clear – in true Heideggerian fashion – that the reader is thrust into confrontation with the Traditioned Voice of Jesus, which requires of him the decision of faith or non-faith, the choice to – by one’s will – become the sinner or the saint. In the same preface, he distinguishes his own theological project from others, claiming that real historical work is not simply recovering the facts of a situation or reconstructing some psychological profile (the programme of the liberal theologians), but allowing a reasonable construction of those facts speak to our innermost selves today: that we might be changed through the crisis of confrontation with these historical realities. To Bultmann, we must allow ourselves to be encompassed fully by God’s Word and Will, and in so doing make the concrete choice to be the saint, to will what God wills.

Bultmann goes out of his way to contrast Jesus’s thoroughly Hebraic message with the surrounding Greek dualisms of His day which posit the world in such a way where neutrality is a real option, claiming:

“With the attitude that obedience is subjection to a formal authority to which the self can be subordinated without being essentially obedient, a neutral position is possible. Man is so to speak only accidentally or occasionally claimed by God, and it is possible to suppose that he might not be so claimed, that this demand of God probably sometimes ceases because it is not an essential element of the human self before God… Hence too there are situations in which it is possible for a man to do nothing – neutral situations. And just this Jesus expressly denies… There is therefore no neutral position; obedience is radically conceived and involves the man’s whole being.”[1]

Bultmann continues a few pages after describing the way in which Jesus’s preached message differed from the Hebraic tradition in which He functioned, and even further critiques any sort of “Hellenistic” understanding of Jesus. He writes,

“The good is the will of God, not the self-realization of humanity, not man’s endowment. The divergence of Jesus from Judaism is in thinking out the idea of obedience radically to the end, not in setting it aside. His ethic also is strictly opposed to every humanistic ethic and value ethic; it is an ethic of obedience. He sees the meaning of human action not in the development toward an ideal of man which is founded on the human spirit; nor in the realization of an ideal human society through human action… the action as such is obedience or disobedience, thus Jesus has no system of values.”[2]

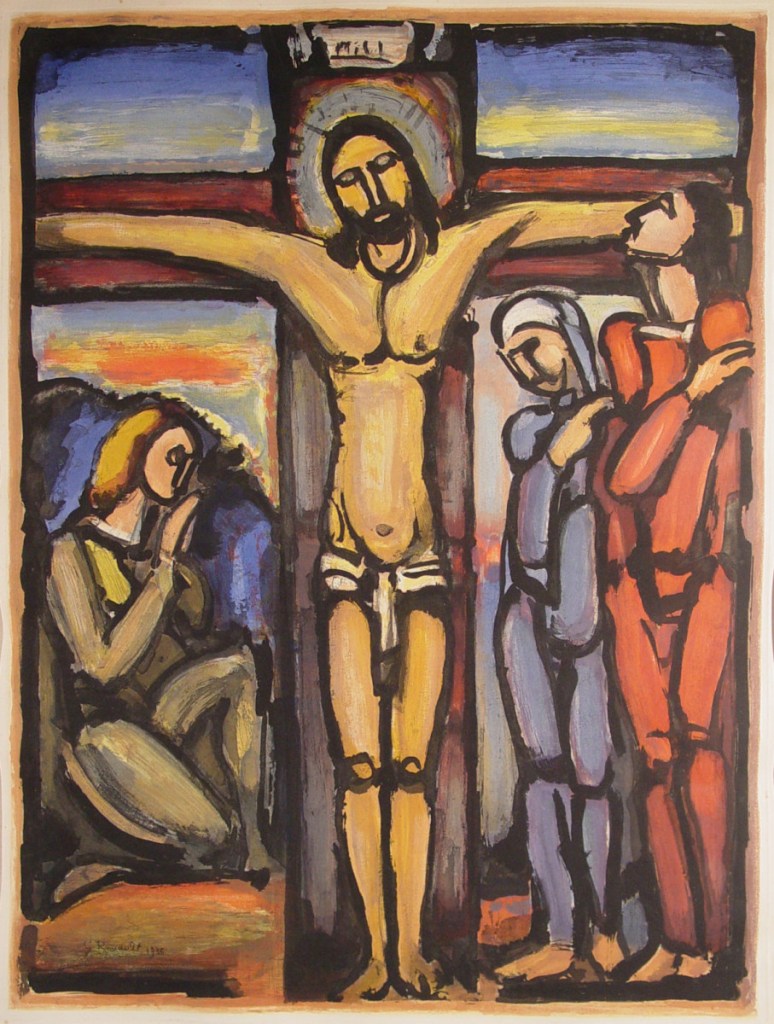

I quite like this quote; I think it cuts against the grain of so much “theological” literature being produced in leftist-leaning seminaries today, as well as in even those seminaries which see one of the primary tasks of the Christian Church as “diversifying its portfolio” if you will, i.e., as using the cross for social justice purposes (which is of course the latest craze).

I think the greatest strength of Jesus and the Word (so far) is Bultmann’s discourses/commentaries on Jesus’s conception of love as obedience, which is wrapped up in his larger theme of decision as obedience. Bultmann has much to say about the simplistic, modernist view of “love,” and decision more generally, as contrasted to how Jesus charges his listeners to love and charity. He writes,

“You cannot love God; very well, then, love men, for in them you love God. No; on the contrary the chief command is this; love God, bow your own will in obedience to God’s. And this first command defines the meaning of the second – the attitude which I take toward my neighbor is determined by the attitude which I take before God; as obedient to God, setting aside my selfish will, renouncing my own claims, I stand before my neighbor, prepared for sacrifice for my neighbor as for God. And conversely the second command determines the meaning of the first: in loving my neighbor I prove my obedience to God. There is no obedience to God in a vacuum so to speal, no obedience separate from the concrete situation in which I stand as a man among men, no obedience which is directed immediately toward God… the neighbor is not a sort of tool by means of which I practice the love of God, and love of neighbor cannot be practiced with a look aside toward God. Rather, as I can love my neighbor only when I surrender my will completely to God’s will, so I can love God only while I will what He wills, while I really love my neighbor.”[3]

Amen and amen, Bultmann. I couldn’t help but think of how Bultmann’s exposition of Jesus’s message of God-love and neighbor-love contrasts with the programme of a man like John Piper, whose explications of “Christian Hedonism” – i.e., “using your neighbor” for a baptized form of self-fulfillment – stands as such a different picture to this one. And this, written by a man who most definitely did not believe Jesus is God, nor God the Trinity!

The dialectical or crisis theologians have much to teach evangelicals today, even if we would shake our heads and yell “Nein!” at so much of the rest of their claims.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus and the Word (New York, NY: Scribner’s Library, 1958), 77-78.

[2] Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus and the Word (New York, NY: Scribner’s Library, 1958), 84.

[3] Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus and the Word (New York, NY: Scribner’s Library, 1958), 114-115.