–

–

T.F. Torrance is one of those theologians you can confidently say is a pretty homogenous writer when his whole corpus is considered. If you have read one of his books on theology – unless it is a highly specific monograph or journal article or something of the sort – you have read them all. This is not to be disparaging of Torrance’s work; he is one of my favorite theologians to learn and glean from. In fact, his sort of repetitive, lets-circle-back writing style fits in with his own theory of language and human understanding. For those who have read a good bit of his output, however, the thought can very well cross your mind when you approach a section you have read two or three times over elsewhere that, “He’s saying this again? Well alright…” Regardless of this aspect, his ideas are meaty and worth wrestling with.

Currently I am reading (for the first time) his Mediation of Christ, the book many veterans of Torrance commend to the newly-interested as the ideal starting place. Torrance has already mentioned Israel’s place in salvation history, Einstein, “onto-relations,” and the conceptual revolution he is convinced is taking hold in the Western world – all topics that fall into the “over-and-over” category – and is making his way to a treatment of Christology proper.

The Christology never gets old, though. Ask any regular reader of Torrance and they will tell you that coming away from sustained attention to his Christological and Trinitarian reflections makes you want to run to Church and perform a praise break. He writes in such a way as to lead his readers to a greater love and affection for the Lord Who has loved them in His own Person. He wants people to praise Jesus, and so he writes to fan the flames of his readers’ hearts.

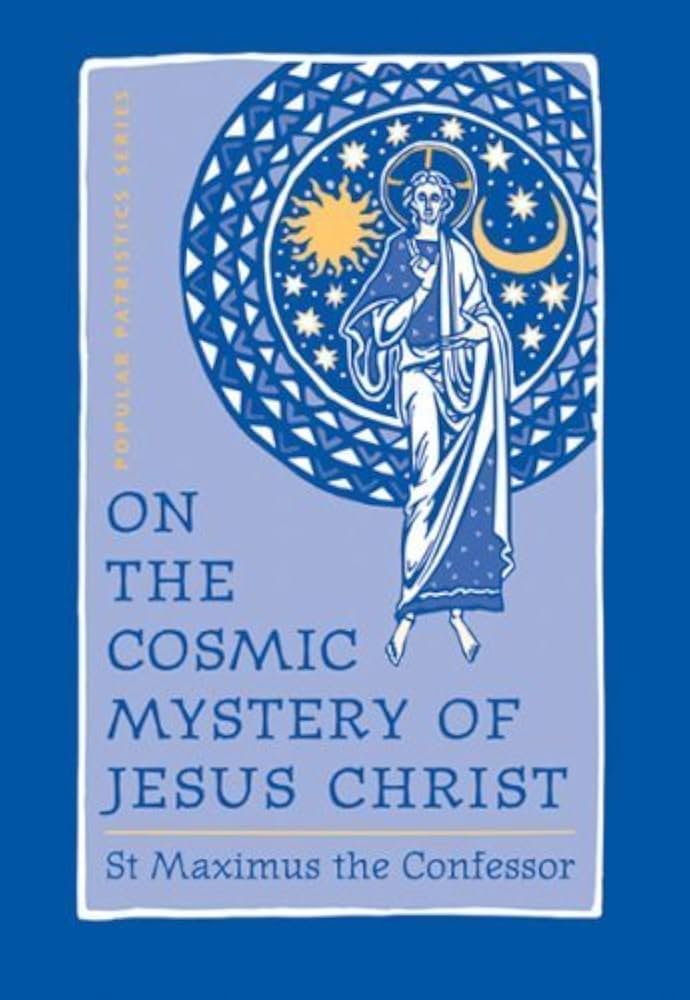

Let us take his chapter, “The Person of the Mediator,” as an example. Here he lays out the importance of the Christian affirmation that Jesus Christ is “God of God, Light from Light,” i.e., just as much God as the Father is God. He says,

“The Sonship embodied in Jesus Christ belongs to the inner relations of God’s own eternal Being, so that when Jesus Christ reveals God the Father to us through himself the only begotten Son, he gives us access to knowledge of God in some measure as he is in himself… Jesus Christ is Son of God in a unique sense, for he is Son of God within God, so that what he is and does as Son of the Father falls within the eternal Being of the Godhead… Jesus Christ is to be acknowledged as God in the same sense as the Father is acknowledged as God, for it is in virtue of his Deity that his saving work as man has its validity.”[1]

Pretty solid, yet standard, Christian language concerning the Divinity of Jesus. So far, so good. Torrance is never content to simply state the official doctrinal language established by the historic Church, however; he is always looking to drive home the pastoral import of these traditional ways of speaking of God and Christ. So, of course, he continues:

“He [Jesus] does not mediate a revelation or a reconciliation that is other than what he is, as though he were only the agent or instrument of that mediation to mankind. He embodies what He mediates in himself, for what he mediates and what he is are one and the same. He constitutes in his own incarnate Person the content and the reality of what he mediates in both revelation and reconciliation.”[2]

Alrighty! So now Torrance is speaking to a question that the average, everyday Christian very well comes in contact with: Who (or what) does Jesus reveal? Himself! Torrance says. There is no reality or God apart from whom Jesus means to point us, since Jesus Himself “constitutes” that God we would look for elsewhere. It is God, in other words, who is on display in Jesus. It is God who heals the blind and cleanses the lepers; it is God who lifts up the poor from the dirt and gives them dignity as persons; it is the Holy One of Israel who condescends as a baby to unite us with Himself. Jesus is Himself the content of His own revelation. Jesus is Himself our salvation, and not simply the one Who points to it, as if it was something other than His very Person.

It gets even deeper, though. What are the consequences of holding a different opinion other than the one just expressed? What if Jesus really does point away from Himself to another reality, another thing called “salvation”? What if Jesus is not Himself God?

“If you cut the bond of being between Jesus Christ and God, then you relegate Jesus Christ entirely to the sphere of creaturely being, in which case his word of forgiveness is merely the word of one creature to another which may express a kindly sentiment but actually does nothing… To claim that Jesus Christ is not God himself become man for us and our salvation, is equivalent to saying that God does not love us to the uttermost, that he does not love us to the extent of committing himself to becoming man and uniting himself with us in the Incarnation… If there is not unbreakable bond of being between Jesus Christ and God, then we are left with a dark inscrutable Deity behind the back of Jesus Christ of whom we can only be terrified. If there is no relation of mutual knowing and being and loving between the incarnate Son and the Father, then Jesus Christ does not go bail, as it were, for God, nor does he provide for us any guarantee in what he was or said or did as to what God is like in himself.”[3]

If Jesus Christ is not the Holy One of Israel, if He is not Himself God, then he is just a creature sending peace and blessing to us, ourselves creatures like him. We might could find a certain moralistic lesson in this, something close to an exemplarist religion where each person is trying his best to correspond himself to the good life, but we would still be in the dark about God. That is what Arius believed, and what current-day proponents of his thought still believe about God. If Jesus is not God, we would still have to guess at the character of the God who he supposedly represents. We would still have to guess whether, at the end of the day and regardless of the many assurances to the contrary, God is not actually just a sky-tyrant whose sole desire is to see humanity suffer and die. There would be no way of knowing this isn’t the case if Jesus is not Himself God.

And why is this? Why does Jesus have to be God for us to know the character of God? Because what Christians claim – what Jesus claimed about Himself – is that Jesus is God come to us as man. He is God, crossed over the divide of being onto our side of things. He is the God stepped from behind the curtain. He has said, “Here I am.”

Furthermore, the Bible’s portrayal of Jesus is one whose delight is in the restoration of people. Everywhere he goes, the Bible tells us, Jesus seeks to heal, restore, and bring to life that which has been destroyed by sin and death. God is good, life-giving, and holy, we know, because Jesus is good, life-giving, and holy.

And thank the Lord that that is true. Thank Jesus (!) that we do not have to guess about who He truly is, but we can rest in His blessed character shown not only among the poor and the widowed and the sick, but upon the cross, where the depths of divine love are on absolute full display.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] T.F. Torrance, The Mediation of Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1983), 64.

[2] T.F. Torrance, The Mediation of Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1983), 67.

[3] T.F. Torrance, The Mediation of Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1983), 68-70.