–

–

Robert Jenson is known for many things: his emphasis on the sacraments, his theological creativity, his reliance on Hegel, his reliance on Barth, his ability to speak theology concisely, and the list goes on. One aspect of his theology I have not seen touched on as much, however, are the new relations he posits the Church should consider as helpful descriptors for how to conceptualize the Triune Life. He affirms quite joyfully the traditional relations – generation, spiration, origination, procession – but proposes that not-before-seen reciprocal relations be recognized as constituting the Spirit’s dynamic contribution to God’s ontology.

ST: The Spirit as Liberator and Reconciler

Jenson introduces the new relation of liberation into the life of the Trinity. He does this so as to heed Hegel’s (and Buber’s) thoughts concerning what constitutes a healthy I-Thou relation. For Jenson and these thinkers, within the isolated person-to-person relationship there can only be a form of obsessive relational domination. If there are only two partners of relation, there can only be a subject-object and hence a master-slave dynamic as the only possible dynamic. This can be plainly seen in the obsession with which abusive partners find others – all others, friends of the beloved perhaps primarily – as threats to the lover’s enjoyment and satisfaction of the beloved. Inversely, the lover whose enjoyment of the beloved because of or alongside of the friends and companions surrounding the beloved is said to be a healthy, relationally-balanced individual. Jenson and Hegel would wholeheartedly agree. The only way the two partners can be freed for their love and enjoyment of one another, they argue, is if a third party opens up the two partners for their mutual love for one another. The Holy Spirit fulfills this function for the Father and the Son, and in so doing is rightly characterized, like Augustine said, as the love-bond of the Trinity.

Jenson writes: “If you and I are to be free for one another, each of us must be both subject and object in our converse. If I am present in our converse as myself, I am a subject who have you as my object. But if I am not also an object for you as subject, if I in some way or degree evade reciprocal availability to you as one whom you in your turn can locate and deal with, I enslave you, no matter with what otherwise good disposition I intend you.”[1]

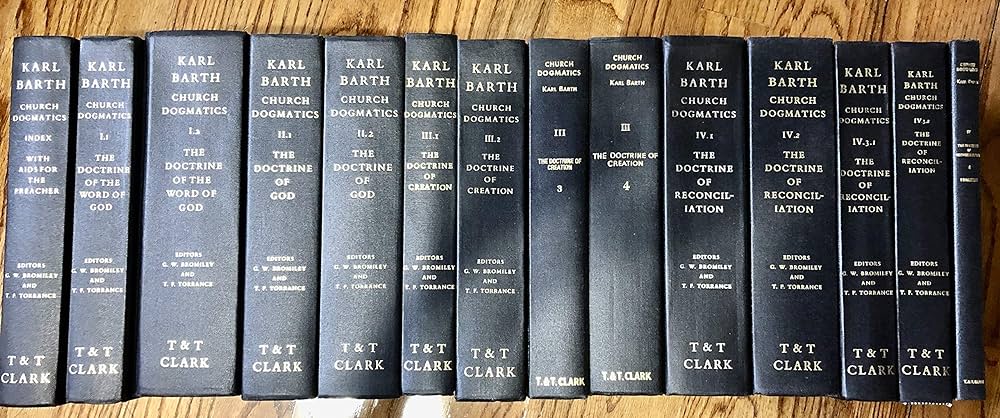

In other words, if Father and Son are not reciprocally available for each-other as Father and as Son in the bond of their Spirit-love, there is no Triune God like the Tradition says. Without the Spirit, there is no true bond or relational openness as constitutive of God’s being, and therefore no true bond between the Son – who simply is the Lord Jesus Christ – and the Father He has been sent from. Jenson is convinced that previous theological missteps were taken in the history of doctrine because of a pre-existing blindness to this relational dynamic of the Spirit. To name a recent example, Jenson thinks that most of what should be criticized in his theological grandfather, Karl Barth, has to do with Barth’s malnourished (and possibly nonexistent) doctrine of the Holy Spirit. He goes so far as to say that, when it comes to the Church Dogmatics, Barth proposes what looks much more like a “binity” than a Trinity.

He further elaborates: “So we must learn to think: the Spirit is indeed the love between two personal lovers, the Father and the Son, but he can be this just in that he is antecedently himself. He is another who in his own intention liberates Father and Son to love each other. The Father begets the Son, but it is the Spirit who presents this Son to his Father as an object of the love that begot him, that is, to be actively loved. The Son adores the Father, but it is the Spirit who shows the Father to the Son not merely as ineffable Source but as the available and lovable Father.”[2]

It is in being the glue of the Father and Son that the Holy Spirit exists as the Tradition’s third hypostasis. “The Spirit is himself the one who intends love, who thus liberates and glorifies those on whom he ‘rests’; and therefore the immediate objects of his intention, the Father and the Son, love each other, with a love that is identical with the Spirit’s gift of himself to each of them.”[3] This sort of change to Augustine’s initial thesis does what Augustine arguably did not do, which was to recognize the personal element in the Holy Spirit’s procession from the Father and the Son. It is not simply as some thing called “the love between Father and Son” that the Spirit acts; such a conception is what led to the plumb line of the West’s depersonalization of the Spirit. It is as the one who, in proceeding from Father and Son, acts to blossom the generation and paternity of Father and Son for each other that the Spirit is a subsisting relation, i.e., as the subsisting relation of openness and freedom.

To conclude:

“The Father begets the Son and freely breathes his Spirit; the Spirit liberates the Father for the Son and the Son from and for the Father; the Son is begotten and liberated, and so reconciles the Father with the future his Spirit is. Neat geometry is lost, but life is not geometrical.”[4]

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology, Vol. I: The Triune God (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997), 155.

[2] Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology, Vol. I: The Triune God (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997), 156.

[3] Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology, Vol. I: The Triune God (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997), 158.

[4] Robert Jenson, Systematic Theology, Vol. I: The Triune God (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1997), 161.