–

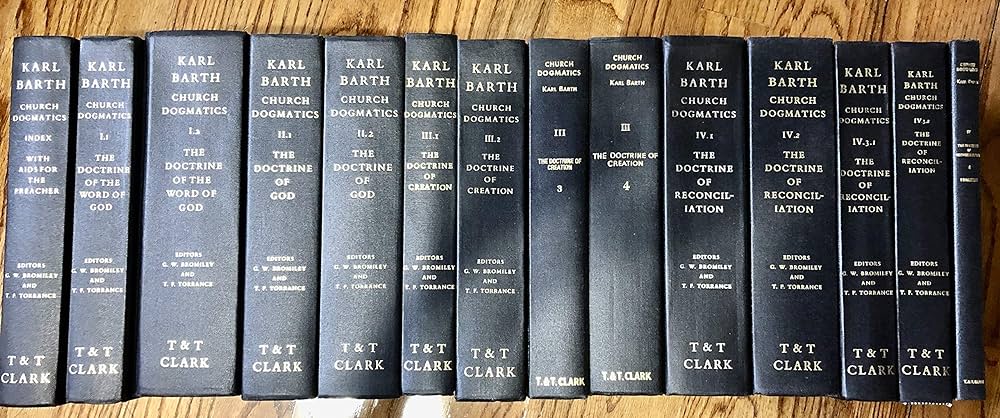

Thomas F. Torrance was a Church of Scotland minister, mentee to the preeminent Karl Barth, and a world-renowned theologian in his own right whose universal appreciation – from all sides of the aisle – points to the man’s formidable theological mind, his heart for people, and a passion for the unity of the twentieth century Church. Personally, I have benefitted enormously from the little amount of meditative reading I have recently done on him, and do not plan to stop reading Torrance until I go to be with the Lord. Along with Barth, he has all but revolutionized my understanding of what Christ has done for the world and how I should subsequently see my place within Christ’s universe; of those I have heard from who have read Torrance with charity, a similar change has taken place in them. Of the Barthians – the term I am using to refer to those theologians which Barth intimately influenced – I think Torrance stands as the most insightful and thought-out theologian, and his evangelistic fervor and obvious concern he had for the pastorate pull on my deepest heartstrings. Eberhard Jüngel, the Lutheran mentee of Barth’s whose place in the hierarchy of those Barth taught falls directly behind Torrance, in my opinion, had a similar but quieter influence on the theological landscape of his day but in mostly Lutheran circles (whereas Torrance was a Reformed man, through and through).

The First Things article titled “T.F. Torrance and the Latin Heresy,” written by a Roman Catholic acquaintance of Torrance’s, presents a clear-cut image and a strong critique of Torrance’s entire theological project. In so many respects like his mentor, Torrance used strongly-worded language when referring to those ideas he perceived to have corrupted the Church’s theological language through the centuries, perhaps the most exciting of which was what Torrance termed the “Latin Heresy.” The Latin Heresy alluded to the Western Church’s continual tendency to adopt theological language which conceptualized God’s relation to humanity in Christ in dualist terms, using ways of speaking which separated being and act, form and content, and, in Torrance’s view, Jesus Christ and God the Father. The Latin Heresy – and the essay Torrance devoted to the development of the idea, titled “Karl Barth and the Latin Heresy” – is what the author of the article, Douglas Farrow, tackles from a Roman Catholic perspective. In what follows I will pull out a few ideas of Farrow’s and Torrance’s and put them in critical conversation, and attempt to work out my own thoughts concerning it all.

As a side note of sorts, I would like to start with a small comment Farrow makes near the middle point of his article. He writes, about Torrance’s value to Christians of other traditions:

“For he [Torrance] is capable, with Barth, of helping Protestants learn how to be critical of Protestantism as well as of Catholicism, and how to enrich themselves with patristic insights and resources. Moreover, Protestants can learn from Torrance something that Barth cannot teach them: a degree of respect for liturgy and sacraments and even for episcopal ministry… Catholics can hardly dismiss Torrance’s critiques as so much Protestant caricature. In Torrance, as in Barth, they are confronted by a Protestant who forces them to think hard about the mediation of Christ in ways they are not accustomed to. On the other hand, in Torrance they can discover points of contact with the hieratic and liturgical dimensions missed by Barth.”[1]

Here Farrow notes something I too have realized about the difference between Barth and Torrance. In many respects, Torrance has a much more patristic flavor than Barth, even considering how heavily Barth leaned on and listened to the Fathers. One can only expect Torrance, then, to have a much higher appreciation for catholic – and here I am very much ready to throw Barth under the rug – sacramental understandings and for the place of structure and order in the Sunday liturgy. The very fact that Torrance’s entire project was constantly emphasized to be founded on the complimentary theologies of Sts. John Calvin and Athanasius of Alexandria points to how highly and explicitly Torrance considered Nicene theology in his approach. Torrance was a thoroughly Nicene theologian, and no one can combat it.

Of course, Farrow then combats it. Before we get to Farrow’s critiques, let us see what Torrance puts forth in thesis form (this is a blog after all) in his essay “Karl Barth and the Latin Heresy.”

To begin with, Torrance outlines Barth’s primary theological input as reminding the Church that “‘God himself is the content of his Revelation,'” as opposed to an instrumentalist or dualist conception of Revelation where God is imparting some thing outside of Himself. He then goes on to lay out theological history as he sees it developing in the West (for the worst):

“What Karl Barth found to be at stake in the twentieth century was nothing less than the downright Godness of God in his revelation, for the Augustinian, Cartesian and Newtonian dualism built into the general framework of Western thought and culture had the effect of cutting back into the preaching and teaching of the Church in such a way as to damage, and sometimes even to sever, the ontological bond between Jesus Christ and God the Father, and thus to introduce an oblique or symbolical relation between the Word of God and God himself. Barth’s struggle for the integrity of divine Revelation opened his eyes to the underlying epistemological problems, not only in Neo-Protestantism and Roman Catholicism, but in Protestant orthodoxy as well. These were bound up with the Western habit of thinking in abstract formal relations, which was greatly reinforced by Descartes in his critico-analytical method, and of thinking in external relations which was accentuated by Kant in his denial of the possibility of knowing things in their internal relations. This is what I have called ‘the Latin heresy,’ for in theology at any rate its roots go back to a form of linguistic and conceptual dualism that prevailed in late patristic and medieval Latin theology.”[2]

Torrance’s primary problem, then, is Western theology’s characteristic tendency to externalize the ontological relations of God in both its doctrine of the Trinity and its doctrine of the Hypostatic Union. Thus, he goes on to say, you see Westminster orthodoxy’s tendency to Nestorian-ize the Hypostatic Union in pursuit of fulfilling their closed doctrinal loop of satieting God’s anger-principle, and, in Roman Catholicism, of constructing an ecclesiology which objectifies God’s grace in an outer-hierarchical-imparted-grace-Church mode. Farrow rightly summarizes,

“Liberal Protestantism… had more or less reduced theology to ethics, and the mediation of Christ to moral influence… In so-called high Calvinism, represented by the Synod of Dort, there had long been a severe instrumentalization of Christ, which both Barth and Torrance spent much energy resisting… British and American Evangelicalism… developed a penal substitution theory of the atonement that has its closest Catholic counterpart in Mel Gibson’s misbegotten The Passion of the Christ.”[3]

Following this critical-historical diagnosis of Western theological thought, Torrance goes on to reveal what he believes is the antidote to the problem. Bringing in St. Athanasius, he further argues:

“My concern here, however, is with the place which Barth, like Athanasius, gave to internal relations in the coherent structure of Christian theology, and of the way in which he exposed and rejected the habit of thinking in terms of external relations which had come to characterize so much of Western theology.”[4]

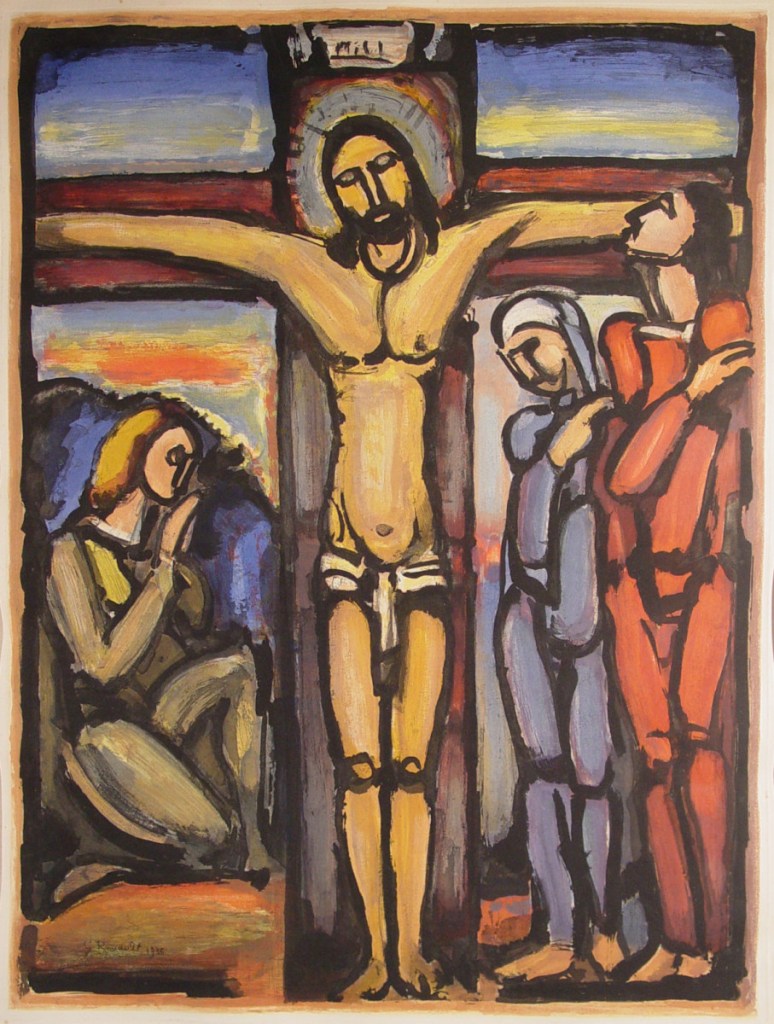

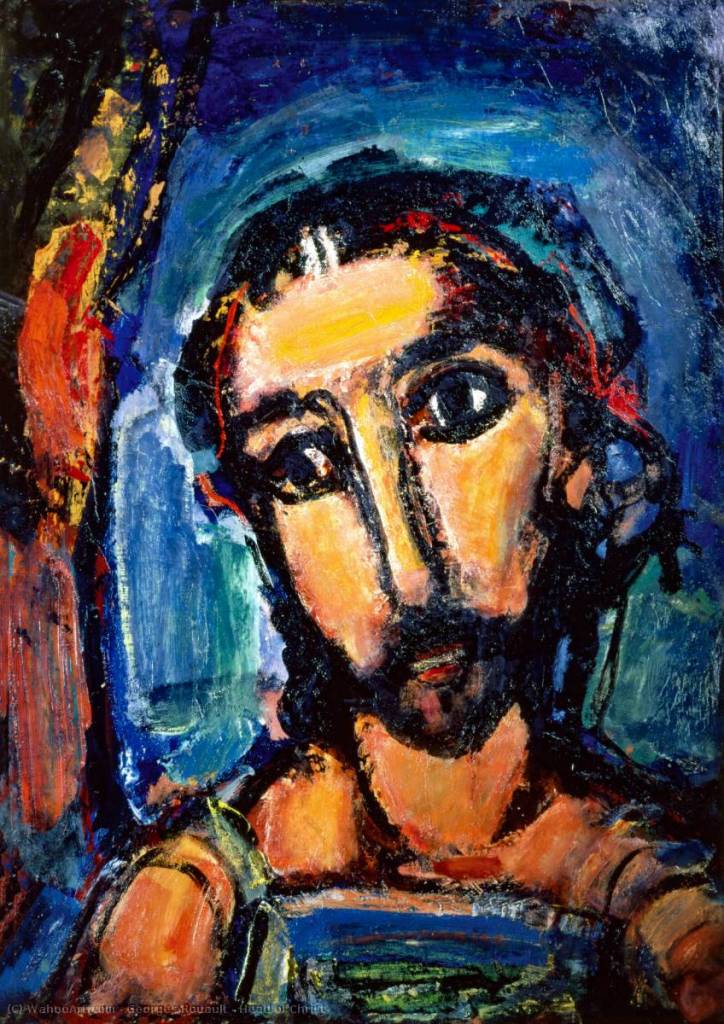

At the heart of Torrance’s and Barth’s critiques of the West have to do with the primary issue mentioned earlier: for God to truly have said to reveal Himself to mankind, for the Christian faith to be truly unique from the rest of mankind’s self-made religious-expressive landscape, for God to have truly said to have united Himself to humanity in his breaking-forth into our limited, corrupted existence in Jesus Christ, there must really and truly be taking place an authentic, Triune, Self-revealing in the event of the incarnation. The externalism of the West obscures and objectifies what God imparts to us, diminishing this central truth of the Gospel that what we have in salvation is relational, since our “salvation” is truly “reconciliation,” i.e., reconciliation with God Himself and not some external legal thing or some external imparted or mediated “grace.”

*Here, I might footnote that a sacramentology which uses language of “imparted grace” does not necessarily then fall into the externalism under discussion, but, understood rightly, further reinforces this truth of the Gospel-centric presencing of God in, through, and with the sacraments.*

Let’s bring in Farrow’s critique. He remarks, after a lengthy appreciation section on Torrance:

“Barth and Torrance have, in part, misdiagnosed the problem and misconstrued the solution… Barth’s imposition on the doctrine of the Incarnation of an actualist ontology – an ontology that already contains and is soteriology – is seen by Torrance as a breakthrough that enables us to shake off the Latin heresy. But it can also be seen as a kind of theological oversteer that puts Christology into the ditch on the Eutychian side of the road… The first consequence of turning Jesus into a reconciling event, into a divine-human Happening that… is everywhere and always taking place, is that the Church becomes nothing more than a community of witnesses, a community of people who with the eyes of faith see and confess what is everywhere and always the case. The sacraments themselves become mere acts of confession… For if reconciliation is an event strictly internal to the being of Christ, and if Christ is without remainder the reconciliation he achieves, then the Church must be denied any reconciling or mediating function of its own, lest it somehow be confused with Christ. Thus the Eucharist, as traditionally understood both in the Latin and the Greek Churches, is incomprehensible – even idolatrous. And the Church remains something hidden. Even in the Eucharist it cannot be said, ‘Here is the Church.’”[5]

I think Farrow is actually on to something here. Although I would push back with his observation that Torrance’s formulation of the Incarnation is Eutychian (it is one of the healthiest, most balanced treatments I have come across of the Hypostatic Union), his ecclesial and sacramental concerns resonate with me. Undoubtedly, what Farrow has in mind in terms of the “mediating function” he wants imparted to the Church looks like the specifically Roman hierarchical structure of which he is a part, but the sentiment behind it is not necessarily wrong. As I noted in my aside earlier, the language of “imparted grace” does not constrict the Christian theologian to a Roman sacramental or ecclesial understanding. The “authority” of the Church can still wholeheartedly be affirmed, apart from the poles of the Roman magisterium or the pietistic, democratic religion prevalent in lower Evangelicalism.

For sake of space, I will cease the discussion here (for now). Farrow will go on to mention his frustrations over Barth’s and Torrance’s Mariologies and perceived historical ignorances. Perhaps I will do a blog post on how rightly I think Torrance and Barth tackle history.

Farrow gives a critically appreciative final thought, the spirit of which I share:

“For my part, I wish to say in grateful tribute: It was he who began to open me to theology as a discipline, to Barth as its preeminent twentieth-century practitioner, and to critical realism as its appropriate epistemological mode. Like many others, I learned from Torrance how to find in Barth what his many detractors had missed or deliberately overlooked. From Torrance (as from Gunton), I learned to see some things that even Barth had overlooked, and so to think independently of Barth. The twentieth century was a century of great theologians, the likes of which we may not see again for a long while, and Torrance must be numbered among them.”[6]

Thomas F. Torrance is worth your time to read. As a Nicene, Trinitarian, Christological, and Ecumenical theologian, he should rightly go down as a contemporary Church Father.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Douglas Farrow, “T.F. Torrance and the Latin Heresy,” First Things, December 2013, pg. 28.

[2] Thomas F. Torrance, “Karl Barth and the Latin Heresy,” Divine Interpretation: Studies in Medieval and Modern Hermeneutics (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2017).

[3] Douglas Farrow, “T.F. Torrance and the Latin Heresy,” First Things, December 2013, pg. 28-9.

[4] Thomas F. Torrance, “Karl Barth and the Latin Heresy,” Divine Interpretation: Studies in Medieval and Modern Hermeneutics (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2017).

[5] Douglas Farrow, “T.F. Torrance and the Latin Heresy,” First Things, December 2013, pg. 29-30.

[6] Douglas Farrow, “T.F. Torrance and the Latin Heresy,” First Things, December 2013, pg. 31.