–

–

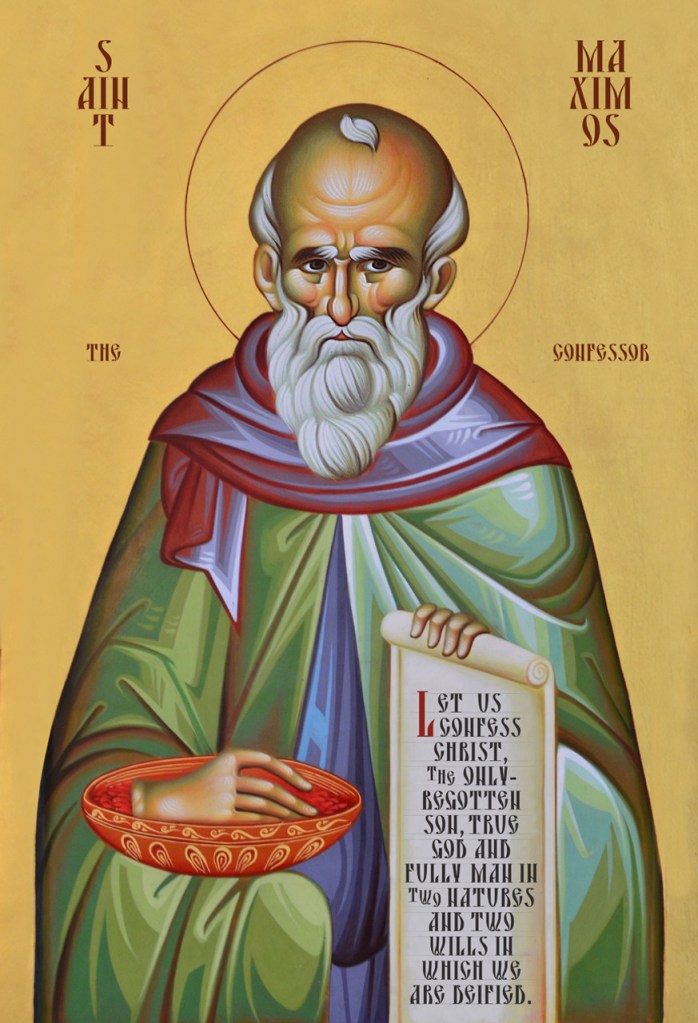

Maximus the Confessor is known as the greatest seventh-century defender of a logically-consistent Chalcedonianism. As the “Confessor” part of his title indicates, Maximus held to the Apostolic Faith at a time when the entire empire opposed it (even if the empire did so unknowingly, which my reading of the history would tend to posit). His greatest contribution to the life-world of the Tradition was his staunch opposition to the notion of one will in Christ and his hard-line advocacy of diathelitism: that Christ, though a single hypostasis, contains two wills in accordance with His two natures. Maximus posited the diathelite position as what he saw as the absolutely essential outflow of an appropriate affirmation of a two natures Christology, and spoke to his interlocutors accordingly.

So, as one would expect, readers of Maximus’s works, particularly his Ambigua, cannot understand Maximus without understanding the theological controversies he considered so central to a living faith. In particular, Maximus is unintelligible without at least a cursory understanding of the doctrine of the Hypostatic Union: that Jesus Christ is both God and Man in mysterious union, as one, indivisible subject. In engaging with this doctrine, however, the responsible reader will note how Maximus – just like all the greatest of theologians – posits the hypostatic union as a reality quite non-static, as instead a glorious, living, active reality which has real and primary import for people living in this fallen world. Central to this doctrinal livingness is what has been termed the “Great Exchange,” that, as Maximus quotes Gregory Nazienzen writing, “He [the Son] receives an alien form, bearing the whole of me in Himself, along with all that is mine, so that He may consume within Himself the meaner element, as fire consumes wax or the sun earthly mist, and so that I may share in what is His through the intermingling.”[1]

This paradigm is quite literally everywhere in Maximus’s writings. For the purposes of this post, I will simply focus on his Ambigua 1-4 in his Ambigua to Thomas.

Maximus defines the Union thus, in #3:

“‘He who is now human was in composite’ and simple both in His nature and hypostasis, for He was ‘solely God,’ naked ‘of the body and all that belongs to the body.’ Now, however, through His assumption of human flesh possessing intellectual soul, He became the very thing ‘that He was not,’ that is, composite in His hypostasis, ‘remaining’ exactly ‘what He was,’ that is, simple in nature, in order to save mankind… It was, then, the Word Himself, who strictly without change emptied Himself to the limit of our passible nature.”[2]

Maximus defines the Eternal Son as “simple” in “both… nature and hypostasis,” which allows Him the divine freedom to act upon the creation without in turn being affected (i.e., the fathers assumption about the simplicity and aseity of divine being). From this position of freedom (a term I am taking from Barth), He then “became the very thing ‘that He was not,'” i.e., humanity, so that humanity could subsequently be taken up in Himself. Maximus ends this paragraph by tying this Great Exchange of divinity with humanity to the latter’s divinization. Here we see where the patristic mind like the one held by Maximus depart from contemporary accounts of soteriology and divine being. Bruce McCormack and the Post-Barthians would read Maximus here as beholden to a definition of divine being and salvation alien to the life-world of the Christian Scriptures. To McCormack, salvation can appropriately be spoken of as union with Christ (in line with his Reformed commitments), but the paradigm of deification brings along with it a whole host of doctrinal baggage concerning God’s nature (like God’s impassibility and simplicity) which he deems problematic. My first instinct is to want to agree with McCormack, but then I see how Maximus places Christ at the center of salvation – in an even more profound and scriptural way than even the Reformed – and I can’t help but exclaim with Maximus: “Yes! The Son did take on my nature, even though simple and impassible Himself!” There must be a stronger man in order for the strong man to be bound.

I am always pleasantly surprised and excited whenever I read in the Fathers some doctrinal point that a contemporary theologian takes such pains to prove or posit as if it had not been argued before in the history of theological reflection. Such is how I felt when, upon reading Ambiguum 4, Maximus claims – just like Barth! – that the location of our knowledge that God is good, that God loves humanity, and that God works to redeem humanity, cannot be found except where God makes those attributes plain: in Christ! Maximus writes:

“If, then, He emptied Himself and assumed ‘the form of a slave’ (that is, if He became man), and if in ‘coming down to our level He received an alien form’ (that is, if He became man, passible by nature), it follows that in His ‘self-emptying’ and ‘condescension’ He is revealed as the one who is good and loves mankind, for His self-emptying indicates that He truly became man, and His condescension demonstrates that He truly became man passible by nature.”[3]

God is the one whose nature is read off the skin of Jesus. God is the one who, in “‘coming down to our level'” and “‘ [receiving] an alien form'” showed Himself to be the good God who loves his created ones, and whose desire is to see them re-united with Him in perfect harmony. Not only that, but this God, “having absolved our penalty in Himself… gave us a share in divine power, which brings about immutability of soul and incorruptibility of body through the identification of the will with what is naturally good in those who struggle to honor this grace by their deeds.”[4]

Lastly, let us consider one final point Maximus makes at the end of his 4th Ambiguum. He writes:

“In doing lordly things in the manner of a slave, that is, the things of God by means of the flesh, He intimates His ineffable self-emptying, which through passible flesh divinized all humanity, fallen to the ground through corruption. For in the exchange of the divinity and the flesh He clearly confirmed the presence of the two natures of which He Himself was the hypostasis, along with their essential energies, that is, their motions, of which He Himself was the unconfused union.”[5]

The profundity of Maximus’s argument here lies in what he claims is shown forth “by means of the flesh.” Maximus’s claim that Christ “intimates His ineffable self-emptying” means that Jesus Christ proved Himself to be God in the manner in which He acted out his obedient ministry among men and towards the Father. He is proved to be God-taken-on-flesh, Maximus claims, in the en-flesh-ment itself, in God acting as Man and Man acting as God. It is the Man-acting-as-God half of that equation that takes the cake here for Maximus, and displays Maximus’s dialectical tendency to – also, similar to Barth – switch his foci between Son of Man and Son of God in one continuous, repetitive emphasis. Further, it is in the “exchange of the divinity and the flesh” that “He clearly confirmed the presence of the two natures of which He Himself was the hypostasis.”

When I read contemporary theologians complain of a tendency in the Church Fathers (that undoubtedly exist in some) to present theological realities as static, scientific things whose complexities must be analyzed, I look to Maximus the Confessor and those like him. Theologians like Maximus tear apart the notion some historians of doctrine give to the history of theological reflection that it is some dry, doxology-less, humdrum activity, and show it to be what it is meant to be: a beautiful, worshipful meditation on the reality of God as shown forth in Christ. Maximus writes, to end: “How great and truly awesome is the mystery of our salvation!”[6]

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Gregory the Theologian, Or. 30.6 (SC 250:236, ll. 5-20).

[2] Maximus the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, ed. and trans. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 19.

[3] Maximus the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, ed. and trans. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 25.

[4] Maximus the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, ed. and trans. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 25.

[5] Maximus the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, ed. and trans. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 27-29.

[6] Maximus the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua, Vol. I, ed. and trans. by Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 31.