–

–

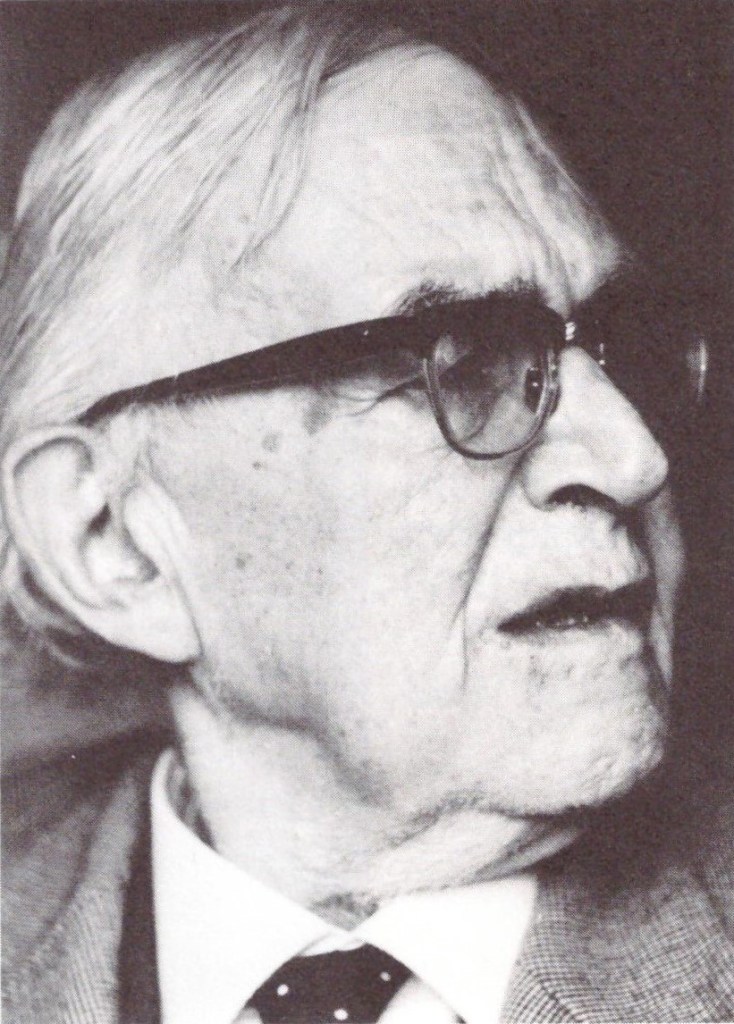

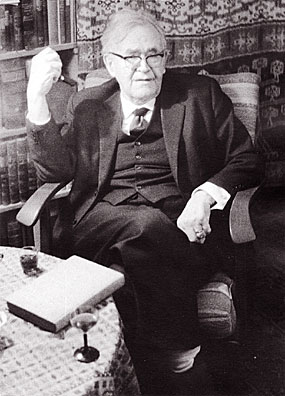

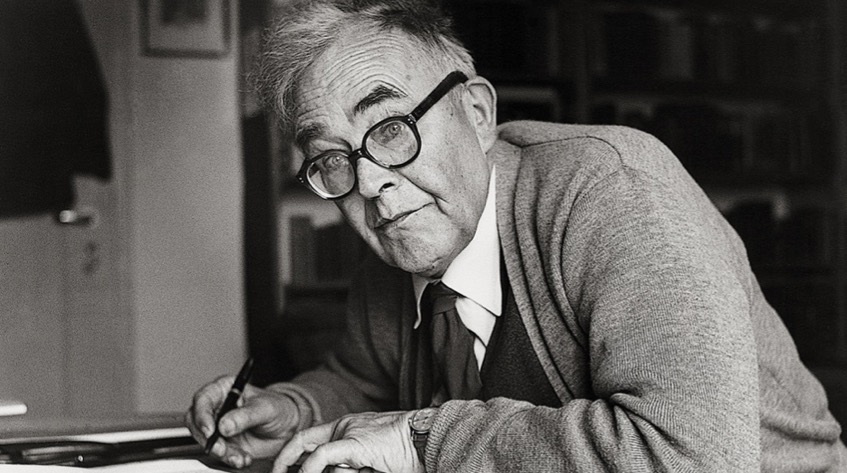

Recently I finished reading a compendium of letters written by Barth during the last seven years of his life. The collection is filled with insider information on Barth’s dealings and correspondences, and it gives the reader rather interesting access to all of his personal and theological preoccupations leading up to his death. For example, I did not know that he was virtually absorbed in the developments of the Second Vatican Council, which was transpiring in the mid-60s; the theologians who were a part of that council, furthermore, were highly influenced by – or at least aware of – Barth’s theology, and sent him an invitation to be an outside observer to the council’s proceedings.

For the purposes of this post, I saw fit to lay before you two letters, both pastoral in nature, which Barth sent to two troubled individuals who had reached out to him about two very different problems.

The first letter was written in late December of 1961, and is a response to a German prisoner whom Barth was fairly sure was contemplating taking his own life. The pastoral counsel Barth offers is a balm to the heart. It reads:

“Dear N.N.,

Your letter of the thirteenth reached me yesterday and moved me greatly. Partly because you refer to my good friend Gertrud Staewen but above all because Christmas is upon us, I hasten to make at least a short reply.

Since you obviously want something from me, you cannot be serious in expecting me to judge you harshly. But can I give you any supporting counsel?

You say you plunge deeply into the Bible in vain. You say you also pray in vain. You are clearly thinking of a ‘final step’ but you shrink back from it. Have I understood you correctly?

First regarding your prayers. How do you know they are in vain? God has His own time and He may well know the right moment to lift the double shadow that now lies over your life. Therefore, do not stop praying.

It could also be that He will answer you in a very different way from what you have in mind in your prayers. Hold unshakably fast to one thing. He loves you even now as the one you now are… And listen closely: it might well be that He will not lift this shadow from you, possibly will never do so your whole life, just because from all eternity He has appointed you to be His friend as He is yours, just because He wants you as the man whose only option it is to love Him in return and give Him alone the glory there in the depths from which He will not raise you.

Get me right: I am not saying that this has to be so, that the shadows cannot disperse. But I see and know that there are shadows in the lives of all of us, not the same as those under which you sigh, but in their way oppressive ones too, which will not disperse, and which perhaps in God’s will must not disperse, so that we may be held in the place where, as those who are loved by God, we can only love Him back and praise Him.

Thus, even if this is His mind and will for you, in no case must you think of that final step. May your hope not be a tiny flame but a big and strong one, even then, I say, and perhaps precisely then; no, not perhaps but certainly, for what God chooses for us children of men is always the best.

Can you follow me? Perhaps you can if you read the Christmas story in Luke’s Gospel, not deeply but very simply, with the thought that every word there, and every word in the Twenty-Third Psalm too, is meant for you too, and especially for you.

With friendly greetings and all good wishes,

Yours,

KARL BARTH.”[1]

The second letter was written five years later, in early December, in response to a German pastor (who was also a former student) who was prompting Barth to be more responsive and appreciative of certain ecclesiastical-political goings-on. The shift changes in this one. Gentle, comforting Barth has been put away and, in his place, the reprimanding, disapproving, fatherly Barth now comes to the fore. It reads:

“Dear Pastor,

Your urgent letter of 2 November still lies unanswered in front of me and so (for the last week) does your fiery poem ‘Germany’s Path,’ which points in the same direction. I thank you for them. Excuse me if I am brief. I am no longer able to draw up longer statements.

This brings me at once to your wish, which you have even presented to me in the form of a citation to appear before the judgment seat of the Lord of the church. Amidst all the speaking and shouting in Germany, loud enough as it is, you want me to issue a kind of roar of the lion of Judah in the style of certain utterances at the beginning of the thirties. Dear pastor, you are not going to hear this roar. ‘For everything there is a season and a time.’ That I am not at one with Bultmann and his followers I have shown publicly and clearly not only in my booklet Ein Versuch, ihn zu verstehen but also in the whole C.D., especially the last volumes. And C.D. is in fact being read quietly much more, and more attentively, than you seem to realize. And since the good Lord, in spite of reports to the contrary, is not dead, I am not concerned, let alone do I feel constrained, to act as the defender of his cause in a confessional movement… For one thing I have other and more useful things to do.

This brings me to the second thing concerning yourself. As you tell me, you have just come from three months of persistent depression in the hospital, and you have already had other periods like it. After this ‘down’ you are not in an ‘up.’ Good, thank God for it, but see that worse does not befall you. It is not thanking God, nor is it good therapy, to use this ‘up’ to proclaim the status confessionis hodie, to imitate Luther at Worms or Luther against Erasmus, to compose thoughtlessly generalizing articles and paltry battle-songs, to write me (and assuredly not only me) such fiery letters, to pour suspicion on all who do not rant with you, indeed, to punish them in advance with your scorn, etc. Instead you should be watching and praying and working at the place where you have been called and set, you should be reading holy scripture and the hymn-book, you should be studying carefully with a pencil in your hand the theological growth springing up around you to see whether there might not be some good grain among the tares. Lighting your pipe and not letting it go out, but refilling and rekindling it, you should not constantly orient yourself only to the enemy – e.g., to seninely simplistic statements such as those recently made bt the great man of Marburg in the Spiegel – but to the matter in relation to which there seem to be friends and enemies. Then in the modesty in which is true power… you should preach good sermons in X, give good confirmation lessons, do good pastoral work – as good as God wills in giving you the Holy Spirit and as well as you yourself can achieve with heart and mind and mouth. Do you not see that this little stone is the one thing you are charged with, but it is a solid stone in the wall against which the waves or bubbles of the modern mode will break just as surely as in other forms in the history of theology and the church they have always broken sooner or later? Dear pastor, if you will not accept and practice this, then you yourself will become the preacher of another Gospel for which I can take no responsibility. You will accomplish nothing with it except to make martyrs of your anger those people who do not deserve to be taken seriously in this bloodthirsty fashion and whom you cannot help with your ‘Here I stand, I can do no other.’ With the modesty indicated, be there for these people instead of against them in this most unprofitable style and effort. In this way, and in this way alone, will you thank God for your healing. In this way, and in this way alone, can you help to prevent new depression overtaking you tomorrow or the day after.

This is what I want to say to you as your old teacher, who also has real knowledge of the ups and downs in the outer and inner life of man even to this very day, but who knows how to greet in friendly fashion the remedy which there is for them.

With sincere greetings, which I ask you to convey also to your wife and sister-in-law,

Yours,

KARL BARTH.”[2]

This last one in particular struck me, as it sounds like something a former version of myself would have done well to listen to.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Karl Barth, “19: To a Prisoner in Germany,” in Karl Barth Letters: 1961-1968, ed. by Jürgen Fangmeier and Hinrich Stoevesandt, ed. and trans. by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1981), 27-28.

[2] Karl Barth, “237: To a Pastor in Germany,” in Karl Barth Letters: 1961-1968, ed. by Jürgen Fangmeier and Hinrich Stoevesandt, ed. and trans. by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1981), 229-231.