The end of my last post includes a quotation from Paul Tillich’s Biblical Religion and the Search for Ultimate Reality which puts forth Tillich’s position on the compatibility between philosophy and theology. The central thesis of this little book is that philosophy and theology can, in fact, coexist, and are, even further, codependent on each other’s relevance and success as human thought projects. As a lay evangelical theologian, I went into reading his work with a cautious skepticism (which I was right to do), but nevertheless found some insights – about both philosophical investigation and theological speaking – which I thought would best be to throw out there and discuss.

A personal note: later this summer, I plan on flying up to Wisconsin to complete an audited class on the patristic doctrine of Participation at an Anglican seminary. My interest in the patristic vision, generally, stirred my interest in this, and so you can imagine that when I got to Tillich’s section on Participation (and our current age’s rejection of the participatory outlook) my interest piqued. He writes,

“In terms of the history of philosophy, it is a nominalistic ontology which has determined philosophical empiricism from the high Middle Ages to the present moment. Being, according to this vision of reality, is characterized by individualization and not by participation. All individual things, including men and their minds, stand alongside each other, looking at each other and at the whole of reality, trying to penetrate step by step from the periphery toward the center, but having no immediate approach to it, no direct participation in other individuals and in the universal power of being which makes for individualization… one thing must be emphasized. It is a view of reality as a whole.”[1]

Indeed, Tillich! While I have serious reservations about the attempts by many contemporary theologians (most of whom stem from high-church backgrounds) to revive the sort of participatory outlook so-long espoused by the Christian tradition, Tillich does a great job here of outlining the general philosophical air we breathe now: one which chokes us on our own scientistic individualism.

In the next chapter, Tillich displays his presuppositions concerning the nature of religion (Christianity including), but says some thought-provoking things that have real theological implications. He writes, concerning man’s tendency to anthropomorphize:

“There is no type of religion which does not personify the holy which is encountered by man in his religious experience… In the moment in which something took on this [sanctified] role, it also received a personal face. Even tools and stones and categories became personal in the religious encounter, the encounter with the holy. Persona, like the Greek prosopon, points to the individual and at the same time universally meaningful character of the actor on the stage. For person is more than individuality. ‘Person’ is individuality on the human level, with self-relatedness and world-relatedness and therefore with rationality, freedom, and responsibility. It is established in the encounter of an ego-self with another self, often called the ‘I-Thou’ relationship, and it exists only in community with other persons.”[2]

What struck me about this section of the reading is the utter truthfulness of his argument. As one who places himself (generally) within the Reformed theological camp, I place a high value on the proposition that humans, when left to their own devices, will 100% of the time fashion idols for themselves. Calvin’s whole “The heart is an idol factory” meets me with a hearty Amen. Humanity does not and cannot go on long without worshipping anything and everything as long as it is not the God revealed in Jesus Christ. We fashion ideological, material, and emotional gods for ourselves like hotcakes: it is our basic function as corrupted beings. Yet, the Eternal Son’s incarnation as Jesus Christ proclaims an insane and wonderful truth to us, that neither does God seek to be an impersonal God to us; in matter of fact, humanity cannot even come to know or understand a God who does not condescend to our human ways of knowing, thinking, speaking, and being. There is a double edged sword brought out by reflection on Paul Tillich’s assertions here: humanity both cannot understand a God who would require them to either transcend or escape their humanity (since there literally is no way for us to know or be known except in ways appropriate to our mode of being), yet humanity continually and doggedly insists on making created puppet-gods who conform to who we believe god should be (which ends, every time, in an anthropomorphized idol).

While there are numerous other sections of the book that I could comment on, I think his page-long discussion of the nature of faith presents some good, final theological-meat to chew on:

“Faith, in the biblical view, is an act of the whole personality. Will, knowledge, and emotion participate in it. It is an act of self-surrender, of obedience, of assent. Each of these elements must be present. Emotional surrender without assent and obedience would by-pass the personal center. It would be a compulsion and not a decision. Intellectual assent without emotional participation distorts religious existence into a nonpersonal, cognitive act. Obedience of the will without assent and emotion leads into a depersonalizing slavery. Faith unites and transcends the special functions of the human mind; it is the most personal act of the person… Biblical faith is the faith of a community, a nation, or a church. He who participates in this faith participates in its sumbolic and ritual expressions. The community unavoidably formulates its own foundations in statements which reveal its difference from other groups and protext it against distortions. He who joins the community of faith must accept the statements of faith, the creed of the community. He must assent before he can be received.”[3]

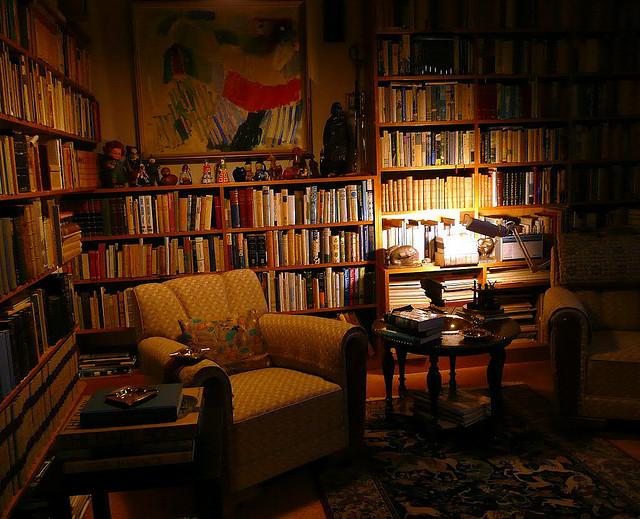

Perhaps this sort of definition of faith is at the heart of my insistence that the center of all theological language be Jesus Christ; it is why I am an avid reader of theologians like Karl Barth, Thomas F. Torrance, St. Athanasius, and the Cappadocian Fathers. Faith, says these figures, is real faith when it is a movement of the Christian’s being, when the intellectual assent which comes through prolonged theological reflection has a purpose and a mission. When simply joined to the ever-lethargic-and-hardly-ever-for-a-noble-purpose school of (in the end, anthropomorphizing) philosophy, theology becomes corrupted by the boundaries of the theologians’ study, the place which should be the locus of ministry and outreach. When evangelicals are lambasted by other sections of the Church on the grounds of some form of anti-intellectualism, I almost want to shout back “Because we have seen how y’all do it, hold’ up in your studies while the widows starve in your pews!” I will proudly wear the badge of anti-intellectual if it means my theologizing must always, always, always have practical ministry application, which is exactly what an absolute Christocentrism will accomplish for the ministry-minded theologian.

Ironically, Tillich realizes the problem that biblical (Christian) theologians have with philosophical speculation’s attempt to wed itself to the theological task. He writes,

“The Bible often criticizes philosophy, not because it uses reason, but because it uses unregenerated reason for the knowledge of God.”[4]

[1] Paul Tillich, Biblical Religion and the Search for Ultimate Reality (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1955), 17.

[2] Ibid., 22-23.

[3] Ibid., 53-54.

[4] Ibid., 56.