The transfiguration is one of those odd episodes in the Gospels which seem disjointed as far as its place in the flow of the narratives go. Immediately before each of the Transfiguration accounts – found only in the Synoptics – Jesus proclaims that he will die, and that those who must follow after Him must follow Him in His treatment at the hands of the religious authorities and the world: that whoever wants to gain their lives must lose them. After the episode, it seems as if Jesus picks up where He left off: healing, traveling, preaching. The story comes as a weird break in an otherwise mostly coherent narrative stream.

–

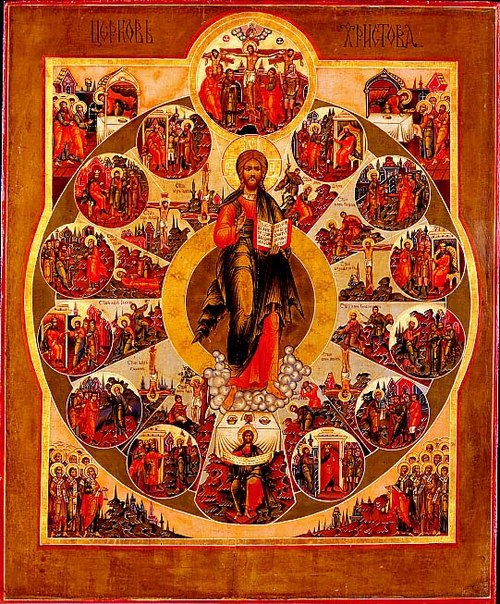

An icon of the Transfiguration.

–

The Lukan account reads, “About eight days after Jesus said this, he took Peter, John and James with him and went up onto a mountain to pray. As he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning. Two men, Moses and Elijah, appeared in glorious splendor, talking with Jesus. They spoke about his departure, which he was about to bring to fulfillment at Jerusalem. Peter and his companions were very sleepy, but when they became fully awake, they saw his glory and the two men standing with him. As the men were leaving Jesus, Peter said to him, ‘Master, it is good for us to be here. Let us put up three shelters—one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.’ (He did not know what he was saying.) While he was speaking, a cloud appeared and covered them, and they were afraid as they entered the cloud. A voice came from the cloud, saying, ‘This is my Son, whom I have chosen; listen to him.’ When the voice had spoken, they found that Jesus was alone. The disciples kept this to themselves and did not tell anyone at that time what they had seen.”

Parallels with Mosaic Narrative

Following this, after Jesus and the disciples descend from this (literal) mountaintop experience, Jesus becomes disgruntled at “this generation” for their lack of faith. What is striking is to note is the parallel movement between this story and the story of Moses’s reception of the Ten Commandments. Both figures ascend to the top of the mountain, where the Word of God and the presence of God are present, surrounded by light and cloud. Then, descending the mountain, they criticize the lack of faith of the people (Moses and the Israelites who have just been worshipping the golden calf and Jesus with the Israelites who are suffering under the weight of their own faithlessness). The presence of Moses alongside Elijah in the transfiguration narrative is striking, too, because he is no longer the protagonist of the story; he is off to the side speaking with the central character Jesus. Jesus is somehow, therefore, a true and better Moses, who is listened to by Moses and Elijah, signaling their inferiority compared to the Christ, to Christ’s mission as central to the fulfillment of the purposes of God.

–

An icon of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments.

–

It has been noted by other interpreters that one difference between the Decalogue narrative and the Transfiguration narrative is the Light that shines from Christ’s face. When Moses is in the presence of God, his face shines, and it continues to radiate as he descends the mountain to rejoin the people. Notice, however, that with Jesus, the light shining from His face is not a refracted light. It is not reflected from some other source, but radiates from Jesus Himself. It is as if the text were saying, “the Source of the light reflecting from Moses’ face in the Old Testament; here is its source!” The voice of the Father – “This is my Son, listen to Him!” – confirms this as well. Jesus truly is “Light from Light,” receiving all He has from the Father, His glory, infinitude, holiness, and righteousness.

Trinity and Spiritual Blindness

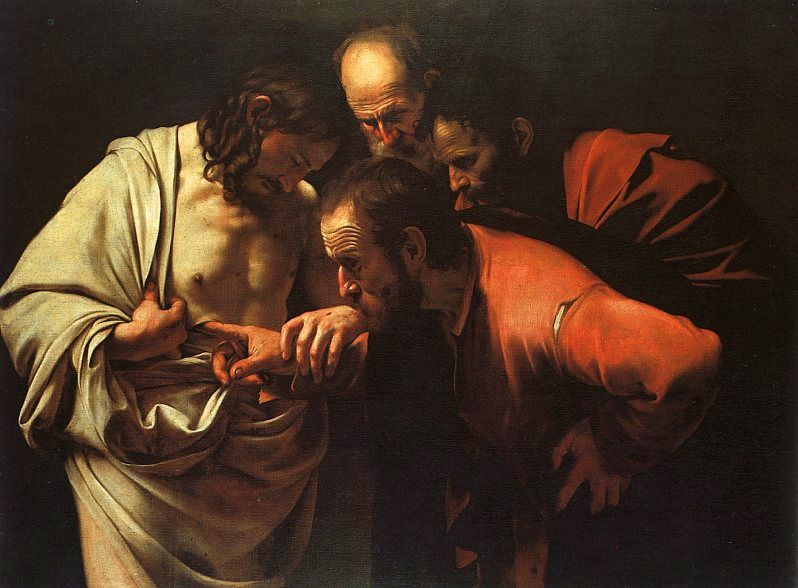

The blindness of the apostles never ceases to give me a disheartening sigh. Nowhere is the inability of man – his utter and total deafness to the Word of God – on clearer display than this scene. The text is clear on what was happening with them: “He did not know what he was saying.” Even during the moment of revelation, the very moment Jesus was shown for who he really was, the apostles did not understand. It is telling, too, that later on, immediately before Christ begins to suffer at the hands of the elders and Romans, Peter – of all people! – attempts to dissuade Jesus from his mission. Peter should have been the first one to have seen that Jesus’s mission culminated and was completed in the suffering he would undergo. It isn’t only that he did not “get it” in the moment of transfiguring on the mountain, its that he misinterpreted who Jesus was after the fact, as well. The text also hints that, just like the Israelites at the foot of Sinai were afraid at the Spirit-cloud (the text says they saw it “as a consuming fire”), so Peter and the disciples were afraid of the cloud and the light: “While he was speaking, a cloud appeared and covered them, and they were afraid as they entered the cloud.”

Notice, too, the similarities to the baptism narrative. Here, again, is the Trinity on full display. The Son, the main character of the story, joined by Elijah (i.e., John the Baptist); the Father’s voice, which, again, points the surrounding listeners to Jesus, displaying His love for and approval of His Only-Begotten; and the Spirit, not in the form of a dove but surrounding the top of the mountain in the form of a cloud, reminiscent of the Spirit-cloud which dwelt on the top of Sinai and which led the Israelites through the wilderness. Here is the Trinity, the fullness of God’s presence. What is man’s response, symbolized by the apostles? Misunderstanding, blindness, and an inability to stay in the presence of God. Adam still cannot stay garden without having to leave it.

We should not be too harsh on the apostles, though. The Bible tells us over and over again that if the Spirit of the Lord does not build the house, the people labor in vain. In other words: no Spirit, no understanding, all the way down. Are we not in the same position as the apostles? Would we have seen – or will we continue to see – Jesus for who He truly is without the intervention of the Spirit, without the Spirit coming to us to open our eyes, to give us the rebirth Jesus says is necessary to enter the kingdom of God? Jesus Himself says, “It is better that I go away, for I am sending to you the One who will call to mind everything I have taught.” Last year I taught theology and church history to groups of ninth and tenth graders. One thing you cannot conclude without surveying the history of the Church is that the Spirit abandoned the Church after Pentecost. There is no activity of the Church – which actually does what is intended, to preach the gospel, to live for others, to see people’s lives changed by Jesus – without the Holy Spirit, because no one can interpret Jesus correctly without the Spirit. Jesus and the Spirit are two peas in a pod; the Spirit’s continual purpose is to point people to Jesus. This then helps us to see this mountain top scene correctly; the apostles do not understand because the Spirit has not given them the eyes to see. Where the Spirit is, there is understanding. If there is no understanding, there is no Spirit.

Revelation of the Son of God

It is not simply the case that the Spirit must flip the switch. We ourselves must also respond. There is still a way in which we are in the position of the apostles. We, like them, can choose to see Him according to the Spirit, or we can choose to see Him according to the flesh. See, the elders, the chief priests, the Romans: they refused to see Jesus according to this picture: the exalted King of Kings who mediates the presence of God and dwells with humanity on the mountain. They could accept that He was a teacher, but they could not accept His claims to be the Son of the Father. They refused to see Him how the Spirit told them to see Him. We are presented with a similar choice.

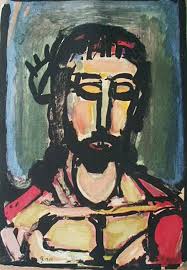

You see, there are many Jesuses which roam this earth. There is the political Jesus, the profound moral teacher Jesus, the comfortable diet hippie Jesus, the hard-nosed masculine Jesus, and innumerable other Jesuses which are very much worshipped and very much followed. None of these Jesuses are the Jesus to whom the Spirit points. Then, there is the Scriptural Jesus. The Jesus that the Church claims to worship; the One who the Nicene Creed says is “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God,” the Only-begotten Son of the Father, full of grace and truth. He is the only Way of Life, the Truth, the Bread of Heaven, the Light of the World, the Lamb Who was Slain before the Foundation of the World, the Alpha and the Omega, and the One who claims our allegiance. This is the One the Spirit wants us to see, know, and love. This is the Jesus of the Kingdom of God. This is the Christ on display in the light of the Transfiguration, the self-interpretation that the Scripture is giving us. Karl Barth writes, “The miracles of Jesus are to be taken as ‘signs’ in the sense that they point to what He already was, to the hidden presence of the kingdom of God which would later be unveiled during the forty days in an abiding manifestation, in a tabernacling of the Lord in the midst of His disciples—a disclosure which will become definitive and universal at the end of all time in His coming again.” The Scripture is so smart, it is always communicating more than we think it is. The Scripture is actually amazing in what it is always doing. The Scripture says here, “That guy, in the Old Testament, who was constantly referred to throughout the pentateuch, the psalms, the prophets, the king who proclaims the word of God on the holy hill of Zion, who is the promised Messiah who will come to liberate Israel and through Israel the rest of the world, who embodies the presence of God to people? Oh yeah, this is that guy. And by the way, this guy – who shines forth the light only God can shine – He will suffer and die as a criminal.” This is why Christ says, right before He goes up the mountain with the apostles, that He would die at the hands of men before then saying, “Some of you will not taste death before [you] see the kingdom of God,” pointing directly to what would immediately happen. It is as if He were telling us, “What you will just hear about – my transfiguration on the mountain – you must understand it in light of what will happen later, i.e., my suffering, my passion, my cross.” Barth confirms this interpretation: “The transfiguration is the supreme prefigurement of the resurrection, and its real meaning will not be perceived until the resurrection has taken place.” This is why the Risen Christ who visits the apostles still bears the marks of His cross in His hands, His side, and His feet. Could He not have chosen to rise again with a fully restored body, without His scars from the cross? Of course! But He is telling us something: He does not want us to know Him as the glorious King apart from knowing Him as the Suffering Servant. He is not king without being servant. In fact, they are one role in Him. He bears the truth he taught His disciples – “Whoever wants to be great in the kingdom of God must be the least of all, must be the servant to all” – in His own Person.

This is the Revelation of the kingdom of God. This is the presence of Jesus: self-emptying love, what Phillipians 2 calls “kenosis.” This is the eternal image of God: this self-emptying, outgoing, reconciling love at work from the creation of the world to the establishment of the New Jerusalem, coming out of heaven for man. And this is the charge for us: will we find ourselves in service to the other? Will we empty ourselves so that love can become actual, visceral even, for those in our lives?

Eschatological Element

Throughout the Scriptures, divine glory always invokes the end of days, in that it always calls people to respond with longing for the Day when God and Man will be perfectly reconciled, when Adam and Eve can once again dwell in the garden forever with God on the mountain. In that sense, the transfiguration is a picture of the new creation; what do we see? We see God in His fullness, shining forth with His glory which tells of His benevolence, love, holiness, and righteousness. And we see Man, perfectly reconciled to the will of God and rejoicing in giving Himself out for God. Jesus is both of these in His own Person, what one theologian calls the “Godward movement of Man and the Manward movement of God.” All of it happens on the top of the mountain, reminiscent of the “holy city” of Zion referenced in Revelation: “And he carried me away in the Spirit to a mountain great and high, and showed me the Holy City, Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God. It shone with the glory of God, and its brilliance was like that of a very precious jewel, like a jasper, clear as crystal” (Revelation 21: 10-11). The transfiguration reminds us of our final destination: to be in perfect unity with God and people in the New Land He Himself has prepared for us. One commentator writes that “those with attentive ears and eyes can and must see it also—hidden glory—in the earthy ministry of Jesus, in the world of human need and gracious liberation that already exists, beginning right now at the foot of the mountain. Forget the booths, Peter; the Messiah has work to do.”

Indeed. The Messiah has work to do.

Kyrie Eleison

Happy thanksgiving!

Carroll, John T.. Luke : A Commentary, Westminster John Knox Press, 2012. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bham/detail.action?docID=3416788.

Barth, Karl. Aids for the Preacher. 1886-1968; edited by Geoffrey William Bromiley, 1915-2009 and Thomas Forsyth Torrance, 1913-2007, in Church Dogmatics (Edinburgh, Scotland: T & T Clark, 1977), 314 page(s).