Karl Barth was the son of a pastor. As such, from a very young age he was intimately involved in the life of the church. When he came of age, he decided he wanted to study theology academically, and perhaps then to go into the pastorate like his father. Eventually, this is what he did. His first post, in the small industrial Swiss town of Safenwil, saw many of his most deeply transformative experiences happen to him. After his academic career came to a close he spent much of his time in a pastoral mode once again, visiting the prison nearest the town in which he resided to preach and teach the Gospel.

During his academic teaching career, being granted numerous professorships – throughout Germany and Switzerland – Barth never got rid of his pastor’s heart. In fact, he always wanted his theology (hence the name “Church” Dogmatics) to serve pastors in their attempts to preach the Word of God, administer the Sacraments, and tend the hurting hearts of their congregations. It is in this mode he delivered his sermon, “Make Me Pure of Heart,” an exegesis of the Matthean Beatitudes.

–

Herr Karl, looking dapper.

–

Like a true pastor, Barth wants his hearers to understand that, in the end, help comes only from God. Our best attempts, motives, social programs, and ministries, fall utterly short of true spiritual healing.

“Many high-minded persons with pure motives and champions of all that is good and true, venture into the darkness of the times; so many flaming outbreaks of new spirit, perchance, among the youth of a city or region; but the fire does not keep on burning, it does not break through, it does not spread farther. One feels more and more as if a mysterious barrier were thrust before us, as if we stood before a locked door which must first of all be opened from within if our endeavors to help are not to remain idle and meaningless gestures.”[1]

The enthusiasms of many young people have gone into the sorts of movements to which he refers. There are no shortages of them today. Barth then clarifies the purpose of this repeated, hopeless feeling; this proverbial beating of the head against the wall. What does God desire, in the midst of this seemingly endless striving? What is his purpose in it? To bring to a head the salvation of humanity, not from the spiritual heights, but from the depths of darkness.

“Perhaps all the many and wearisome exertions and efforts which we put forth are the last sure proof of our illness; as for example, in severe sickness the fever rises before the crisis; perhaps in the very distress of all these struggles and efforts something very simple, great, and healing for us must, and finally will, break through; a deep, clear, all-embracing knowledge of that which alone helps… The Bible at all events sees things in this light. ‘Immediately after the afflication of those days,’ so Jesus begins the passage in which He speaks of the everlasting help which shall make an end of all the sorrow of time and of the world; help, salvation, and deliverance really are the final end; but days full of affliction, days full of fear will precede this last end. Such was the experience of Jesus. Before the light of Easter stood the cross and the journey to Jerusalem. The place where all things change is not a height, not even a plain, but an abyss. And the greater the changes the greater the depth from which they arise.”[2]

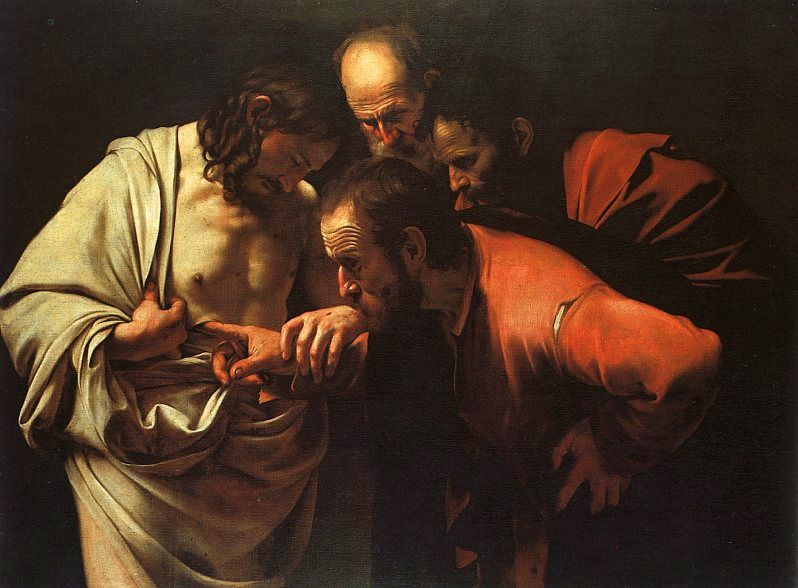

I think of the moment during the eucharistic liturgy where, immediately following the fraction (the “breaking” of Christ’s body), the priest declares, “Christ our passover has been sacrificed for us! Therefore let us keep the feast!” In this moment, the priest lowers the host, breaks it loudly for all to hear, and raises it up again, giving his declaration. Here, the life of God is poured out to the world through the broken body of the Lord. Glory and life is found, not in a pacified trinitarianism, a social program of loveliness, but in the broken body of the God-man. Those who would gain their life must lose it for His sake. Life comes through death. We must commend ourselves to God – we who live in the deep darkness – to be healed.

–

The fraction

–

He continues:

“It seems to us to be too simple; and we are still too much distracted, too little gripped and penetrated by the seriousness of our condition to commend ourselves wholly to God as the only efficient helper of our lives. We are still too spiritually rich, too wise, too gifted, not to desire any other knowledge than that God helps. We are still not poor enough, not humble enough to permit this assurance to enrich and exalt us… Gladly would we permit ourselves to be helped in all our suffering and need, but again helped only by something human, by help which we can understand, which comes from us, and which is in accord with us. But just this cannot be.”[3]

We do not realize our condition. We must be brought low to be lifted up again. We must be destroyed to be recreated.

We will finish where Barth does: “He says it and what He says must be true, namely, that at the very place where we see only our affliction and our sins, only misery and death, there and just there we shall see God. This assurance can only hear, we can only believe, we can only wonder at, when it is told us again and again.”[4]

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

Kyrie Eleison

[1] Karl Barth, “Make Me Pure of Heart” (Sermon), in Karl Barth: Spiritual Writings, ed. by Ashley Cocksworth and W. Travis McCracken (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 2022), 202.

[2] Karl Barth, “Make Me Pure of Heart” (Sermon), in Karl Barth: Spiritual Writings, ed. by Ashley Cocksworth and W. Travis McCracken (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 2022), 203.

[3] Karl Barth, “Make Me Pure of Heart” (Sermon), in Karl Barth: Spiritual Writings, ed. by Ashley Cocksworth and W. Travis McCracken (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 2022), 204-5.

[4] Karl Barth, “Make Me Pure of Heart” (Sermon), in Karl Barth: Spiritual Writings, ed. by Ashley Cocksworth and W. Travis McCracken (New York, NY: Paulist Press, 2022), 207.