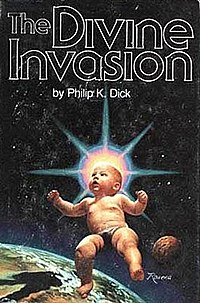

The Divine Invasion is Philip K. Dick’s second book in the VALIS trilogy. Written near the very end of his life, the book is an interweaving of Dick’s final meditations on metaphysics, spirituality, and theology with some of his earlier narrative motifs.

This is how the goat-creature sees God’s total artifact, the world that God pronounced as good. It is the pessimism of evil itself. The nature of evil is to see in this fashion, to pronounce this verdict of negation. Thus, he thought, it unmakes creation; it undoes what the Creator has brought into being. This also is a form of unreality, this verdict, this dreary aspect. Creation is not like this and Linda Fox is not like this. But the goat-creature would tell me that… Gray truth, the goat-creature continued, is better than what you have imagined. You wanted to wake up. Now you are awake; I show you things as they are pitilessly; but that is how it should be. How do you suppose I defeated Yahweh in times past? By revealing his creation for what it is, a wretched thing to be despised. This is his defeat, what you see – see through my mind and eyes, my vision of the world: my correct vision (Dick, The Divine Invasion, pgs 227-228).

The Divine Invasion includes much of what I loved about Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and reminded me why I started reading PKD. The way he introduces one or two primary male characters who drudge through the inescapably terrible world, simultaneously harboring an impure thought life while wrestling to become purer and be at one with the ordering principle of the universe. While in Do Androids Dream Dick’s usually-singular male character is split into two in Rick Deckard and John Isidore (Deckard acting out the immoral or impure role and Isidore the somewhat naive but still heroic trope), The Divine Invasion acts out two parallel stories of similar veins, one at the localized human level and the other at the archetypal, divine level. God himself becomes the split personality, while the human Herb Asher has to deal with the changing tides of the god’s inter-dimensional actions and wrestle with his own choice to act valiantly despite his perceivably unforutunate circumstances (typified, by him, by his endlessly sick wife, Rybys).

Side Note: I couldn’t shake the impression that the characters Emmanuel and Zina were inspired by Leto II and Ghanima Atreides from Children of Dune by Frank Herbert. The way the two children’s dialogue sounds more like philosophy-filled embodiments of the author’s own thoughts in narrative form, and the generally gnostic and meta-human impression they give to the reader point to this comparison. As much as the divine-child narrative trope is worthily used to act out certain incredible aspects of the Divine Son’s Incarnation, I can see how much some of these author’s misunderstand the essence of the Christian doctrine itself; especially as it relates to the humanity of Christ. What I mean is, one of the most incredible markers of authenticity of Jesus’s humanity is his growing up into maturity clearly argued for in the biblical texts. When authors like Herbert and PKD leave out that aspect of their God-Man characters, the divine side, so to speak, overtakes the human side and therefore places the character beyond relatability. It is not a big negative of the story, but an aspect of theology worth considering.

Dick has a great ability to show forth the inherent potency of the divine archetypes. Dick’s knowledge of what people respond to archetypally acts as his primary navigation in his storytelling. The way he makes the character Linda Fox function, for example, is a perfect demonstration of how Dick can intersect the themes of sexuality, femininity, desire, and emotional consolation in a character to evoke in the reader a sort of foundational, wordless understanding. Dick’s characters are embodiments of humanity’s universal feeling towards archetypes like the Great, Consoling Mother, the Harsh, Judgmental Father, the Tempter, the Wise Desert Sage, etc. Something about these character types speak to us, and Dick knew it. Any reader, for example, can empathize with Herb Asher’s morning meditation on Linda Fox (who, in this scene, is the fleshly incarnation of the tender aspect of the divine Being, the feminine side of God named Zina):

Has anyone loved another human as much as I love her? he asked himself, and then he thought, She is my Advocate and my Beside-Helper. She told me Hebrew words that I have forgotten that describe her. She is my tutelary spirit, and the goat-thing came all the way here, three thousand miles, to perish when she put her fingers against its flank… she consoled me, she consoles millions; she defends; she gives solace. And she is there in time; she does not arrive late (Dick, The Divine Invasion, pg 233).

Needless to say, PKD knew what he was doing utilizing these sorts of figures.

It is a hard thing to review a book like this one, especially since PKD fundamentally eludes traditional categories of analysis. As any PKD fan can attest to, Dick’s stories aren’t so much about the details of the world he has “built” within them (in fact, its almost the point sometimes that the details are fluid); Dick’s primary interest is the relationship between the Mind of the protagonist/reader with the shifting reality of the literary world. That said, I think there exists certain strands of beauty and truth interwoven throughout the novel which merit a detailed and meditative read by fans of science fiction (and philosophy) generally. The questions PKD asks (but doesn’t necessarily answer) like What is reality?, What is truth?, What is God?, and What are humans? is enough for anyone to benefit from Dick’s takes. While I don’t think attributing a numerical rating to The Divine Invasion appropriate considering all these ways he eludes such a rating, I think anyone would benefit from reading the book, and think storytellers, in particular, would do well to utilize the sorts of embodied Forms Dick utilizes in this book.

One negative aspect of The Divine Invasion, I will say, which is really applicable to most of his novels (and something I have noted before) is Dick’s pretty terrible portrayal of women. Although the example I gave above (of Linda Fox) appears a positive portrayal of women, it really acts more as a sort of commentary on the “universal” of femininity, and less on women particularly. The sort of a priori-accepted sexual obsession Herb Asher shows to Linda Fox despite the immanent presence of his wife does not do anything to teach the reader, and frankly should disgust them. You would expect that negative trait of Asher’s to be deconstructed over the course of the story and Asher to realize how foolish and disrespectful he has been towards his wife (who you can only really feel pity for), but the final scenes try to portray Asher’s eventual hook-up with Linda Fox as a positive development. I think this really does show a concrete example of Dick’s analytic evasiveness, since the very person who functions the most like the Blessed Virgin (the Virgin Mother of Jesus) is the most unlike Her and the most unpleasant, while the person whose personality best resembles the Virgin is the one who, ultimately, plays the role of the seductress. While portraying specific woman characters negatively isn’t by default immoral (many great villains in stories have been women), the way Herb Asher completely and continually disregards the woman to whom he is married does not translate into any discernible lesson or embodiment of virtue. A question then comes to mind: What constitutes an effective use of archetype? This example would seem to point towards a traditional use of archetypal figures and narrative forms, yet it remains to be seen how they can be utilized in unique ways to teach the good ol’ truths of the universe.

So, what do you think? Have you read The Divine Invasion? Do you think PKD is a beneficial read?

*To read my review of VALIS, the first book in the VALIS trilogy, click here.

Dick, Philip K. The Divine Invasion. New York, NY: Timescape Books, 1981.