–

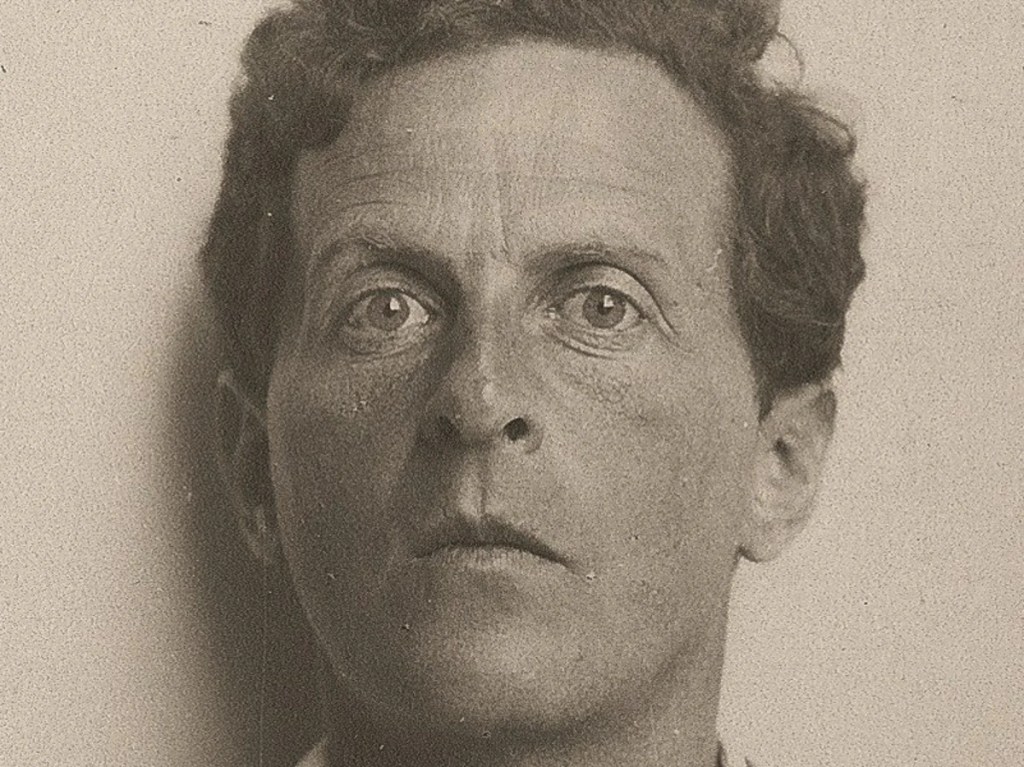

This post will be a bit out of place in connection with the web of posts I have spun on this blog so far. At the moment, I have three literary stallions in my mental pen: Barth’s Church Dogmatics 1/I, Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. These oddly-placed but preeminent texts have a similar inner principle at work throughout each one’s many pages: the centrality and all-encompassing reality of the Word. In Barth, the Word is the Word of God, the sovereign Lord who events Himself in limited human speaking so as to bring human language into itself and allow it to participate in its ontological Truthhood. In Heidegger, the Word is – as his pupil and apostle Hans-Georg Gadamer claims – the always-before-and-evermore-permeating source of Dasein’s being-in-the-world, the being-generating reality. In Wittgenstein, the Word is the system of language games continually, creatively played with and reconfigured and bequeathed at every moment in every community, which also, similar to Heidegger, acts as the reality-encompasser.

Something I have recently been struck by in all three of these thinkers’ texts is that their emphasis on the spoken/written word as the reality-generator of all human experiential/societal being, is that wrapped up in such a world-conception is this rejection of the classical Ancient view (which extended into the Cartesian view) of the “inner-outer” distinction. In Heidegger this is especially seen in his dogged affront against the I-Thou world-picture.

The “inner-outer” conception of human and world ontology can be described roughly by inspecting our Western language surrounding things like the “Mind” versus the “body,” or the “body” and the “soul” distinction. It can further be seen in the subject-object world-conception (what I called the I-Thou world-picture above) in how Western speaking generally tends towards terminology which designates human persons as something like embodied-minds which are unencumbered or uninfluenced or undiscovered in their substantive existence within the world. To the philosophers I have mentioned, such a world-picture is out of step with how language has genuinely been investigated to be. In the course of the development of philosophy of language – i.e., what has preoccupied philosophers for the past few hundred years or so – language has been found, after Kant, to be the fundamental mode of being for (to use Heidegger’s phrase) “Dasein,” i.e., “being-there” (the term Heidegger uses for human persons).

I don’t mean, in this post, to wholeheartedly sign onto and proselytize for Heidegger’s philosophical programme, much of which can be equated with Buddhist thought and language, but to make the distinction I think should rightly be made by contemporary theologians worthy of the name, that: theological inquiry, investigation, and reflection is still very much alive without the ancient house in which it has lived for so long. In other words, to come back to a consistent theme of mine: theology can very much survive on its own without the yoke of ancient ontological categories and pagan-derived world-conceptions. As my friend and I discussed just this past week, the claim made by so many philosophers today about the centrality of language as the all-encompassing, permeating and determining world-creator is by no means contradictory to St. John’s claim (which is frustratingly always associated with Greek philosophical ontology) that Jesus Christ is the Word of God who was “with God in the beginning.” I very much see theologians like Barth, T.F. Torrance, John Webster – and even others like Eberhard Jüngel – as contributing to this new and exciting theological direction.

Why did I name this post “Language and Liturgy,” though? Because, to transition, I see this newfound understanding and appreciation for human speaking as the way in which we can today appropriate genuinely-discovered theological/philosophical insights to best lean into the theological life-world of the Church today. I see one ancient continuity towards this end in the liturgical life of the Church. What I mean is to say that perhaps one of the best things to push today is for a more liturgical expression of the Church’s life so as to combat certain conceptualizations of inner-outer understandings of personhood that has developed into what we see now in what Barth calls “pietistic-rationalistic Modernism”[1] (prevalent in both “conservative” and “liberal” veins of Church expression). Language is the key to overcoming a non-theological, Greek-derived world-picture where the human person is divided in two, instead of mysteriously and wholly united (a central affirmation of the Chalcedonian definition). The spoken word of the liturgy, as our ancient Christian brothers and sisters continually emphasized, is the place in which the communal life of the Church enters into the Person of Christ and is so drawn up into the Triune life so as to fashion us more and more into the Word of the Θεανθροπος.

–

–

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] Karl Barth, The Doctrine of the Word of God: Prolegomena to Church Dogmatics, being Vol. I, Part I, trans. G.T. Thomson(Edinburgh, UK: T & T Clark, 1963), 36.